This is my third and final post about KZ-Gedenkstaette Buchenwald, and concentrates on the memorials at the site. The first two can be accessed below by clicking on the links

So much has changed... (I)

So much has changed... (II)

For all the discussion that has gone into how one remembers the crimes of National Socialism, most memorials tend to be very similar in tone and appearance. They tend to be simple, grey structures, rectangular and exact, their plainness emphasizing perhaps, to borrow Hannah Arendt's book on the Eichmann Trials, the banality of evil. One thing however is constant in memorials in West Germany, and that is that they are a commemoration of the dead, not a celebration of the survivors.

I walked the two kilometres from the KZ-Gedenkstaette Buchenwald to the memorial erected by the Soviet Union in the 1950s. I expected something reasonably celebratory, and had seen pictures of the bell tower and the commemorative statue of a group of survivors, their torn garments hanging from them, crying out in triumph. The Bell Tower, in 1950s Socialist-realist style, seemed slightly out of place, as if it belonged on a Soviet university campus rather than in the middle of Germany.

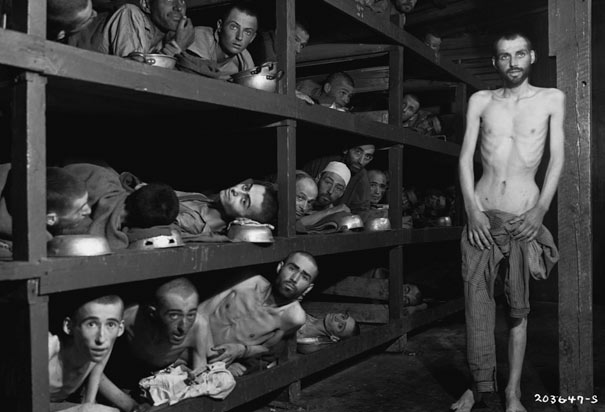

I wandered over to the statue, and saw this...

I was stunned. It is not so clear from the photo but this is just one of two amphitheatre-shaped structures joined together by a row of what look like empty plinths that extend for at least half a mile. I didn't know what to think, or indeed feel. This was the kind of memorial that you simply could not imagine in Dachau, not least because Dachau simply isn't big enough. The architecture seemed almost neo-classical, the style you would have expected of a memorial to Goethe, Schiller and Romantic Germany but not for a place where thousands of people died of arbitrary starvation and maltreatment, victims of two different ideologies united in human brutality.

I descended the steps, stopping every so often to admire the scenery. Just as I had been shocked at how beautiful Dachau and Flossenbuerg looked, Buchenwald was built in a wonderful area. One could imagine this area being taken over by the usual group of anorak wearing enthusiasts who come out and wander the German countryside on weekends. Like other memorial sites however, this land has been tainted.

This memorial feels like an anachronism. I do not know what to do, as I slowly walk among the plinths. Each one has the name of a nation which had citizens in Buchenwald, and shows its age with nations such as Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union still represented. I then notice that there is another row of flagpoles, empty, as well as what looks like a fire-holder (I do not know the name!) on top of each plinth. Then I realise: this is part of the memorial site itself, no longer an 'active' memorial but as an example of how people used to remember! Twenty five years ago, this was still in use and a functioning memorial. Now it stands almost abandoned, a relic of another age. I know memory is politicised, but this is shocking all the same, to see how memorials really do have a sell-by-date.

Time is getting on and the Sun is beginning to set. I walk slowly back to the bus stop, still slightly shocked by this place. I begin to think about the memorials in Dachau, which have aged but are still in use. Will they one day be removed and replaced with new ones, or simply discarded as relics of another age? Will this be the Versoehnungskirche in forty years time, when the survivors have all gone, the historical immediacy of the Holocaust has begun to decline and the Bavarian Protestant Church decide they want to withdraw funding?

Such thoughts are quickly dismissed; I am overreacting. Memorials are constantly changing, adapting. I think back to earlier in the day during our tour of the site. Just by the Jourhaus is a recently installed memorial that is never covered by snow, whatever the weather. It is a memorial plaque which, similar to the old Soviet memorial, is covered with the names of nations affected by KZ Buchenwald. However, this memorial is warm. We are welcome to touch it, rest our hands on the surface. It is kept at a constant temperature of 37 degrees centigrade, the body our bodies need to be at in order to survive. This is a completely different attitude to a memorial. It looks like all the others, yet the way in which people reach down to touch the memorial, warm their hands, is profoundly affecting. Then I think again; should a memorial warm visitors? Either way, it offers a new attitude to engaging with memorials. The Soviet-era memorial has become a relic due to its pomposity; it is out of touch with the people who are commemorating the site, and if we are honest wasn't really built with people in mind. Modern memorials are fully aware that they represent a dialogue between past and present.

Visiting KZ-Gedenkstaette Buchenwald was an emotionally draining experience, more so than I thought it would be. Firstly, the site was bigger than I was used to. Secondly, the history was something both familiar and distant, and it felt at times as if I was learning about the system for the first time, not merely hearing the experience of another site in the same system. Finally, I could see first hand another battle of Vergangenheitsbewaeltigung,, of coming to terms with the past that had taken place in the East as well as in the West. Whilst the Eastern remembrance culture was dominated by the prevailing communist need to re-write history, the Western equivalent seemed to be run by the capitalist need to forget it, so that new houses and factories could be built on what was very fertile land. As ever, there were more questions than answers. Just as it should be.

Later on, we met again as a seminar group to discuss what we had seen. Our group consisted of people from nations such as Hungary, Latvia, Bosnia, Italy, Belarus and Peru among others and each one of us had a different opinion on what we had seen. Once again, it was moving to consider that when I was born this kind of dialogue would have been almost impossible to facilitate. So much has changed in such a short space of time, and despite the differences in our upbringing and what historical baggage we brought to the discussion we were able to talk about the past like adults and as equals. That really is something quite special.